The Changing Shape Of AI Workloads

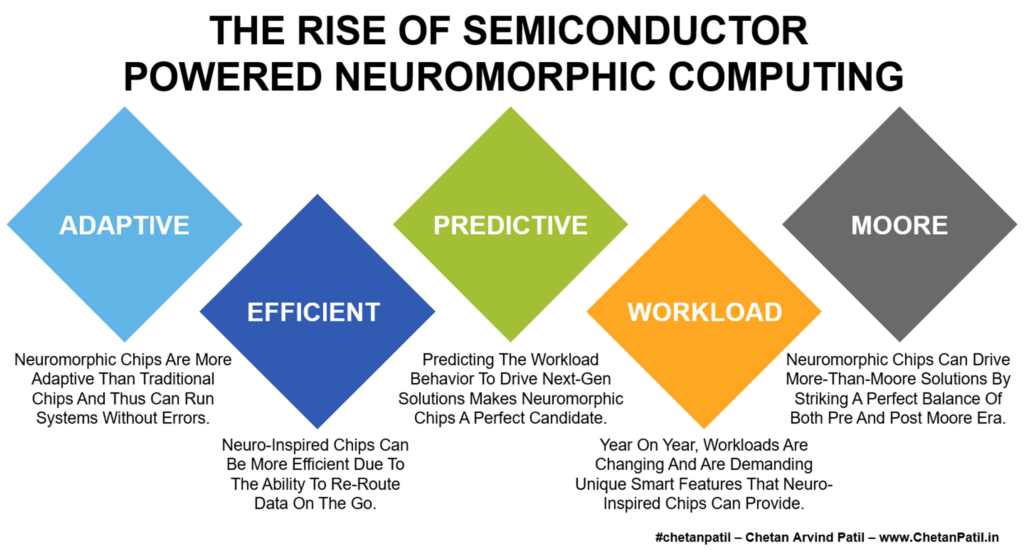

AI workloads have rapidly evolved. They have shifted from lengthy, compute-intensive training runs to an ongoing cycle. This cycle includes training, deployment, inference, and refinement. AI systems today are expected to respond in real time, operate at scale, and run reliably across a wide range of environments. This shift has quietly but fundamentally changed what AI demands from computing hardware.

In practice, much of the growth in AI compute now comes from inference rather than training. Models are trained in centralized environments and then deployed broadly. They support recommendations, image analysis, speech translation, and generative applications. These inference workloads run continuously. They often operate under tight latency and cost constraints. They favor efficiency and predictability over peak performance. As a result, the workload profile is very different from the batch-oriented training jobs that initially shaped AI hardware.

At the same time, AI workloads are defined more by data movement than by raw computation. As models grow and inputs become more complex, moving data through memory hierarchies and across system boundaries becomes a dominant factor. It impacts both performance and power consumption. In many real deployments, data access efficiency matters more than computation speed.

AI workloads now run across cloud data centers, enterprise setups, and edge devices. Each setting limits power, latency, and cost in its own way. A model trained in one place may run in thousands of others. This diversity makes it hard for any one processor design to meet every need. It pushes the field toward heterogeneous AI compute.

Why No Single Processor Can Serve Modern AI Efficiently

Modern AI workloads place fundamentally different demands on computing hardware, making it difficult for any single processor architecture to operate efficiently across all scenarios. Training, inference, and edge deployment each emphasize different performance metrics, power envelopes, and memory behaviors. Optimizing a processor for one phase often introduces inefficiencies when it is applied to another.

| AI Workload Type | Primary Objective | Dominant Constraints | Typical Processor Strengths | Where Inefficiency Appears |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Training | Maximum throughput over long runs | Power density, memory bandwidth, scalability | Highly parallel accelerators optimized for dense math | Poor utilization for small or irregular tasks |

| Cloud Inference | Low latency and predictable response | Cost per inference, energy efficiency | Specialized accelerators and optimized cores | Overprovisioning when using training-class hardware |

| Edge Inference | Always-on efficiency | Power, thermal limits, real-time response | NPUs and domain-specific processors | Limited flexibility and peak performance |

| Multi-Modal Pipelines | Balanced compute and data movement | Memory access patterns, interconnect bandwidth | Coordinated CPU, accelerator, and memory systems | Bottlenecks when using single-architecture designs |

As AI systems scale, these mismatches become visible in utilization, cost, and energy efficiency. Hardware designed for peak throughput may run well below optimal efficiency for latency-sensitive inference, while highly efficient processors often lack the flexibility or performance needed for large-scale training. This divergence is one of the primary forces pushing semiconductor design toward heterogeneous compute.

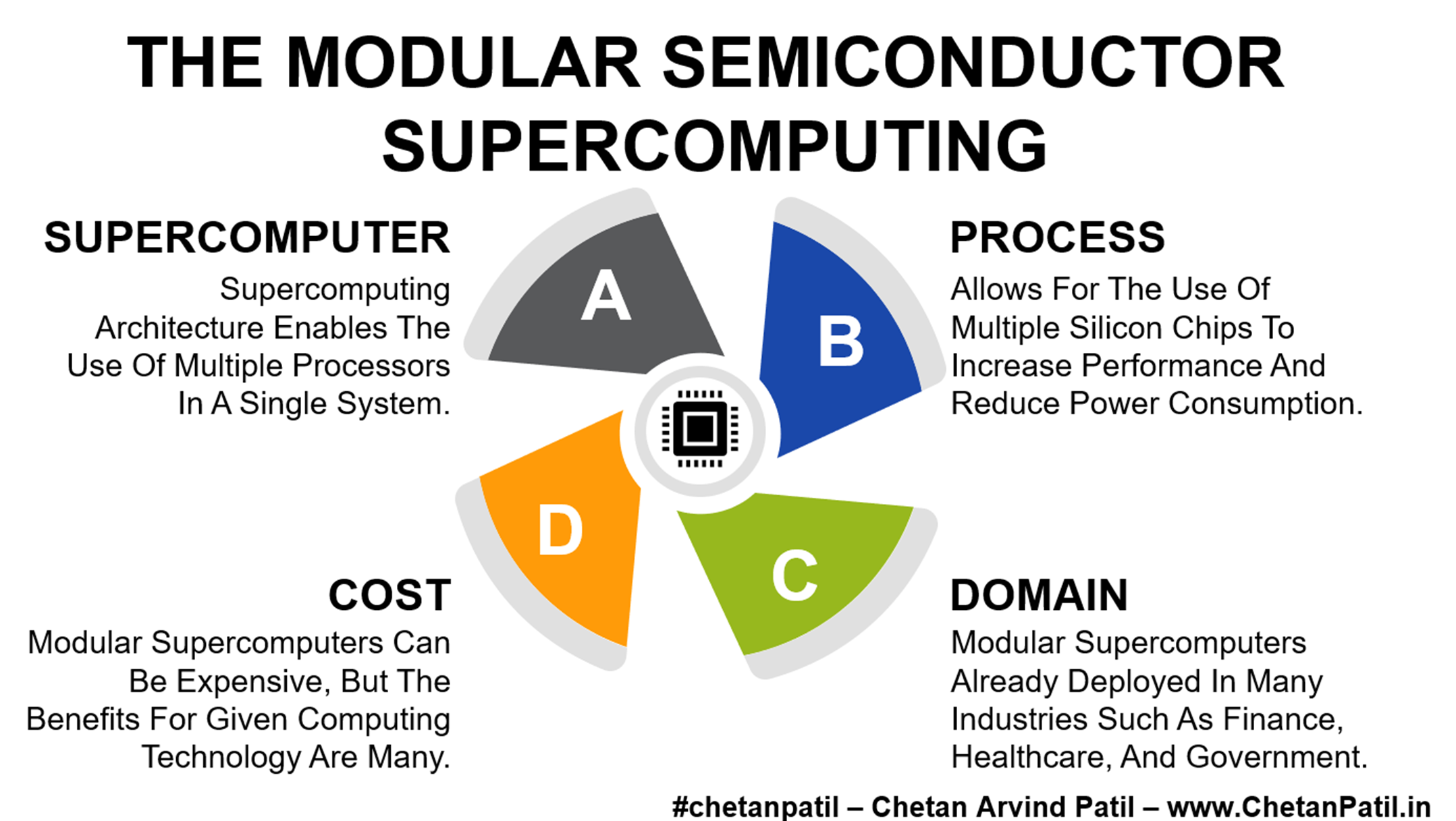

What Makes Up Heterogeneous AI Compute

Heterogeneous AI compute uses multiple processor types within a single system, each optimized for specific AI workloads. General-purpose processors manage control, scheduling, and system tasks. Parallel accelerators handle dense operations, such as matrix multiplication.

Domain-specific processors target inference, signal processing, and fixed-function operations. Workloads are split and assigned to these compute domains. The decision is based on performance efficiency, power constraints, and execution determinism, not on architectural uniformity.

This compute heterogeneity is closely tied to heterogeneous memory, interconnect, and integration technologies. AI systems use multiple memory types to meet different bandwidth, latency, and capacity needs. Often, performance is limited by data movement rather than arithmetic throughput.

High-speed on-die and die-to-die interconnects help coordinate compute and memory domains. Advanced packaging and chiplet-based integration combine these elements without monolithic scaling. Together, these components form the foundation of heterogeneous AI compute systems.

Designing AI Systems Around Heterogeneous Compute

Designing AI systems around heterogeneous compute shifts the focus from individual processors to coordinated system architecture. Performance and efficiency now rely on how workloads are split and executed across multiple compute domains, making system-wide coordination essential. As a result, data locality, scheduling, and execution mapping have become primary design considerations.

Building on these considerations, memory topology and interconnect features further shape system behavior. These often set overall performance limits, more so than raw compute capability.

Consequently, this approach brings new requirements in software, validation, and system integration. Runtimes and orchestration layers must manage execution across different hardware. Power, thermal, and test factors must be addressed at the system level.

Looking ahead, as AI workloads diversify, heterogeneous system design enables specialization without monolithic scaling. Coordinated semiconductor architectures will form the foundation of future AI platforms.